Moving over imagined ground

Our Director of Learning and Head of Schumacher College Dr Pavel Cenkl blogs on his thinking and experiences in the field of Movement, Mind, and Ecology.

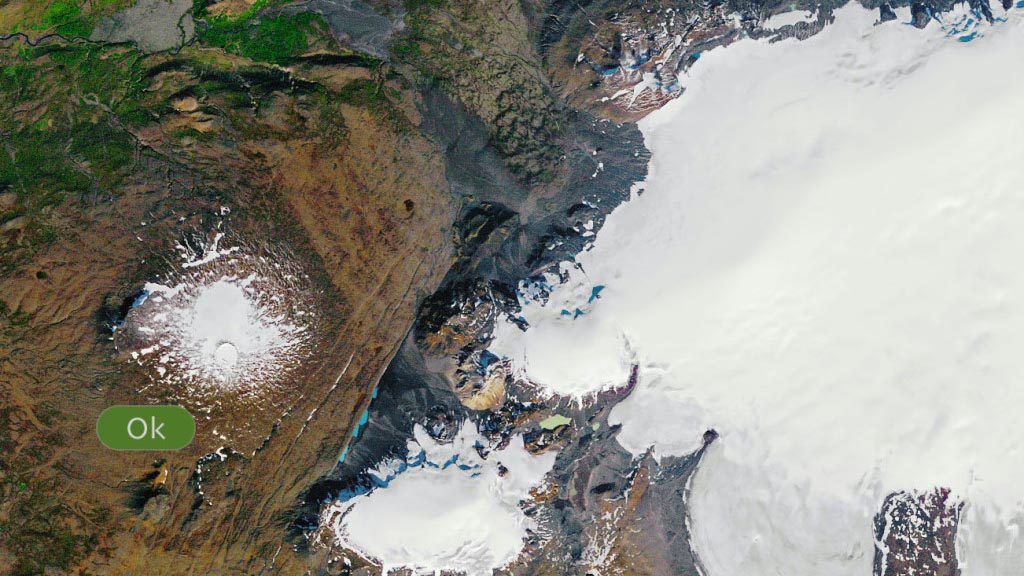

On the undulating gravel highlands between Iceland’s Vatnajokull and Hofsjokull icecaps and, nearer by, the Hágönglón and Kvislarvatn lakes swollen in summers with pale blue-gray meltwater, is the low, rounded gravel summit of Skrokksalda. The summit plateau is home to one of Iceland’s many GPS monitoring site. This one, SKRO, has measured some of the most rapid instances of isostatic (or postglacial) rebound in the world since it began logging data in September 2020.

In recent years, rebound at this site has averaged 20 mm (or not-quite-an-inch) per year due to rapid melting of the nearby icecaps. Between 1994 and 2019, as a whole, Iceland’s glaciers have lost nearly 16% of their volume at a rate of approximately 10 billion tonnes per year.

In June of 2015 on the second day of a three-day trans-Icelandic run, I found myself on the western edge of the highlands, leaning into a headwind that threatened to push me over, spitting rain like needles against my skin. Here, at the top of Haldidalur pass, I briefly took refuge behind a boulder and looked west up the eastern slopes of Ok, a beautifully symmetrical shield volcano that had until the year before, been home to Okjökull (‘jökull’ is Icelandic for ‘glacier’). Okjökull is the first Icelandic glacier to have completely melted away in the Anthropocene and whose disappearance can be clearly tied to anthropogenic climate change. Photo comparisons show a dramatic decrease from the glacier’s extent of about 20 square kilometres in 1900 to its complete disappearance by 2014.

10 billion tonnes is impossible for me to imagine and too easy to subside into a homogeneous blur of meltwater churning gravel on its braided course to the sea. I am more comfortable in what is immediately underfoot — the moments and spaces in which we build resilience, rebound, and momentum for our next step. I can understand 20 millimetres far better than I can 10 billion tonnes.

In Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel’s expansive volume, Critical Zones, dozens of authors explore the almost impossibly thin inhabitable layer on our planet that supports life — and its often messy interweaving of politics, ecology, language, culture, bodies, data, and love. In the Anthropocene this zone is as much about place as it is about relationship. In our engagement with place through various movement practices (we are always moving after all — even when we lie perfectly still — whether through the rise and fall of our our own breath, or running across the open moor, or submerging ourselves in the cold March sea — our movement precedes us, interbraids with our bodies, and persists like so many ripples in meltwater pool.

Movement is always a relational experience.

Much like extended cognition considers our active engagement with the cognitive experience outside ourselves, extended mobility is a recognition of the local and global movement networks of which we are all (often unknowingly) a part.

When my nearly inevitable participation in an economic system that contributes to the climate change that in turn precipitates the melting of Iceland’s glaciers which leads to a measurable rise in the earth’s surface — then that 20 millimetres of annual uplift atop Skrokksalda becomes an expression of the whole of our tangled and messy relationship with the world.

Hardly static, the world presses back at us at every turn — inviting us to explore, inhabit, and celebrate the aliveness of that space between the visible world and another that is constantly in flux — one that is co-created through movement, through relationship between us and the more-than-human world.

Our dance with the world never stops, and our rhythm grows ever more complex.

This blog was written by Dr Pavel Cenkl, the Director of Learning at Dartington Trust and Head of Schumacher College, and programme development lead for the MA Movement, Mind, and Ecology programme.