Our Man in Guatemala: Nathan Einbinder on his agroecology research

We caught up with Dr Nathan Einbinder programme lead for our MSc Regenerative Food, Farming and Enterprise, following his research trip to the Maya Achi territory. Read on to find out how Nathan has been continuing his work in collaboration with local agroecologists, exploring the value of ancestral, indigenous practices from the region and how they might help inform our approach to the food system here in the UK. You can also listen to the audio conversation between Nathan and Will Kemp, Marketing Lead for Schumacher College, via our podcast channel.

Alfredo Cortez, founder of the local agroecology association ACPC (Association of Committees of Community Production) in Guatemala, standing in front of a water catchment recently installed behind the home of one of his members.

Will: Tell us about why you went to Guatemala and the work you were doing there…

Nathan: Well, I’ve been working there in the same village for about 15 years. Actually, not the same village, but the same territory called the Maya Achi territory. So I started working there in 2007 for my Master’s and then just carried through working with different organizations in certain villages in particular. I’ve maintained friendships there and colleagues and done some research. This last time I went specifically to see some friends that I haven’t seen in a while and to find out what their projects are up to, mainly in agroforestry and coffee, and community agroecology projects that focus on food security and diversification, and also planting trees.

I wanted to see what they were doing since I hadn’t seen them in a year. I also wanted to work on two projects specifically. The first project was based on an article that I published in the spring about indigenous soil management practices. And it was in English. It was the last paper from my doctorate, my dissertation. And I started feeling like all the research I was doing there – I was publishing mainly in English, they were academic papers that were pretty inaccessible – and I wanted to do something different, and publish in Spanish, but also publish with two of my main folks there that helped me do the research; have them as co-authors. So the idea was to go back and meet up with them again, talk to them about the results of the study in the paper and the list that they helped create with me about practices.

What we did was we went through each practice and thought about whether this practice was introduced by outside groups or an ancestral practice that had been passed down generation to generation. And we made the list and we noted if it was ancestral or introduced, some of the practices were actually quite mixed because they were introduced so long ago and modified.

And then we started talking about a paper that they would want to co-author, like, what’s the message they want to put out? And so we started working on that.

And the second project is a book chapter that I’ve been asked to write. And again, I want to write it with local people. So there’s going to be three more authors down there. And the chapter is looking at the role of native crops in the indigenous food system. So there are a lot of crops there that kind of spring up semi-wild or have been cultivated kind of on the side or wild harvested. And I mean, we’re talking hundreds of crops potentially, but they’re not well documented and a lot of them are not being used anymore because of complex processes and cheap food being shipped in, namely, changes in culture, migration, all things climate change, poor soil, deterioration of soil, which kind of stops the process of these plants regenerating.

So we want to get an inventory of all the plants and then start looking at the plants and seeing which ones are still being used, what are the dishes that come out of it, and then which plants are at risk and create a study around that. So I started that. But they’re going to continue doing research there while I’m here.

Alfredo Cortez’s own agroecological plot, also used as a demonstration/learning site.

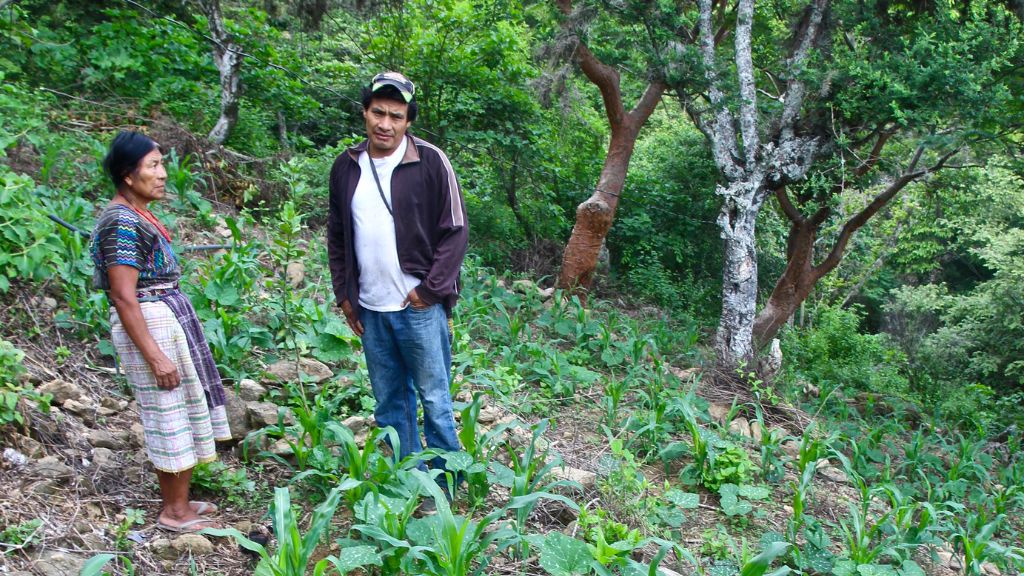

Alfredo with an ACPC member in her milpa (corn, beans, squash) agroecosystem.

Will: That’s interesting that in both cases you’re thinking about collaboration much more strongly. It’s something that I think runs through everything we do at Schumacher College. You know, it’s not about ‘me and my research’ but about us working together to be more effective and more true, I guess, to real life situations.

Nathan: Definitely. There’s just such a weird history down there, and I was playing part of it. I’ve tried to be as collaborative as possible; I’ve lived in the community, not that I’m Achi or can even speak that language, but I feel like I’m a bit more close to them than most researchers that show up for a couple of months and then leave.

But I was still extracting information, publishing, and, you know, advancing my career. And it started to feel really strange. They’ve always been very supportive of my research. A couple of the people I’ve talked to about the soil article weren’t even really that interested. It’s kind of it’s just a bit of a job for them and they already know all this stuff. And I kind of suspected that, but I still wanted to do it and the extraction of, you know, richer nations and more educated people coming down into these areas and pulling information out and just publishing is strange.

Will: And it becomes a kind of exploitation, I guess?

Nathan: Yeah. Kind of just a colonial extension of colonial processes, even if they’re, you know, not sacking minerals or wealth out of there. But in a way, I’m sacking wealth; knowledge.

Will: I wonder why Guatemala? I mean, obviously it sounds fascinating and there’s lots of research to do there, it’s maybe untouched in terms of research to an extent. But how did you end up there in the first place?

Nathan: So I ended up there in the first place on a human rights delegation with other students. Specifically to tour areas that were being impacted by Canadian mining companies. Canadian mining companies have the subsurface rights in like 40% of the entire country. They’ve been sold off by the Guatemalan government to them at a very low price to own the subsurface in private property everywhere. So they go in there and they send in their geologists and look around and find deposits. And then they start working with local people to get at it. And I don’t think I’ve ever come across a case where it fared well for local people. And one mine in particular that was owned by a company called Goldcorp. I mean, we’re talking tens of millions of US dollars of gold being taken out in this community. They’ve left now and there’s just a massive open pit of the headwaters of the river, and these people are just living around it in absolutely terrible environmental conditions. And the company got very rich, left, and that’s it. So we were interviewing people who were in resistance to it; people had been shot and killed. I ended up in the community where I work on a different kind of case. But the guy who was leading us around, this guy, Graham Russell of an organization called Rights Action took us to a community that had been evicted in the early 1980s by a large hydroelectric dam. So that was one of the cases that we were looking at, even though it was unrelated to the mining but it was just very similar story.

So we ended up there and I kind of felt a closeness to the community and a strong interest. And that’s where I ended up doing my Master’s research. And then since then, I just keep going back and developing friendships. It’s not a place that tourists go, especially if you go in the wrong time of year, it’s kind of horrible, hot, dusty. There’s a lot of bad poverty situations, especially in urban areas. But they have retained a lot of agricultural knowledge that’s really interesting.

Milpa agroecosystem, with reforestation project

Agroecosystem with healthy organic coffee plants

ACPC meeting space for knowledge sharing.

Will: And useful, perhaps. I mean, I wonder if we can bring it back to the question of what can we learn from them and what is the relevance for us both here at Dartington and the broader agriculture sector in the UK?

Nathan: That’s kind of the second part of the reason why I went really, was to start thinking about that and writing about it. So I’m going to be working on an article that’s not academic, but it could turn academic down the line. Thinking about how these principles down there can be applied in areas where transformation is happening, transition, and a strong interest in regenerative or agroecology – yet have lost a lot of the ancestral practices in crop varieties. So England is a good example of that. I would argue that there’s more here than people think about, for example hedges or some of the ancient crops or even animal husbandry; animals and legumes. And wheat have been here for thousands of years. There’s got to be some remnants. So some of that stuff I’m thinking about. But the principles of these food systems are really interesting in terms of what we can learn from them. Farmers there, for example, they eat what they grow. And when I tell them down there that farmers appear generally don’t even eat the food that they grow they think it’s absolutely insane. They don’t even understand it.

So the people are so intimate with the production because they eat it and it’s part of their culture and everything. So elements like that are interesting to think about. Another element that’s interesting is, is how connected the food and the growing practices are.

The food, you know, dishes, the rituals behind it, connecting directly to how they’re cultivated, at least in the pure indigenous kind of methods. There’s a lot of stuff that’s come in over the last 30 years that kind of broke that. And, you know, the reliance on traditional knowledge of the land is also quite interesting. And finally, I was looking at the way that knowledge right now in the agroecology movement there is spread. It hasn’t worked well with a top down approach. In other words, an expert coming in and telling them what’s good for the soil, what this crop is good for, ‘you should do this’, hasn’t really worked all that well for them. So they’re kind of building these networks of farmer-to-farmer teaching that I think we have a lot to learn from here. That’s really what my main focus would be: to try to integrate those ideas and empower farmers to be innovative, empowering farmers to be proud of what they’re doing, and to rescue, to recuperate some of these ancestral principles, crops and values. That’s the kind of stuff I want to think about here.

—

Dr Nathan Einbinder leads the MSc Regenerative Food, Farming and Enterprise at Schumacher College, the first postgraduate course in the UK to offer exclusively agroecological approaches to farming and food production. This degree is part of a broader regenerative farming and sustainable horticulture programme at Dartington and you can use the buttons below to explore the different courses we offer.